Learning from Basson judgement

17 April 2014 | Story by Newsroom

It took thirteen years, but Wouter Basson was finally found guilty of unprofessional conduct for his leading role in the covert Project Coast in December last year by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA).

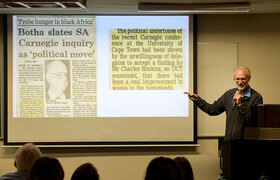

Basson led the apartheid government's chemical and biological weapons programme from the 1980s to early 1990s. A UCT seminar, held in commemoration of Human Rights Day, explored what ethical lessons the medical fraternity could learn from the HPSCA judgement.

"In 1997 Basson was arrested on drug charges involving the illegal sale of Ecstasy tablets. This led to the discovery of three trunks of top-secret documents that were critical both to the TRC's investigation and to a criminal case against Basson," said Professor Leslie London of the School of Public Health and Family Medicine, which hosted the seminar.

"In the criminal case, Basson was eventually acquitted of all the charges [that] included murder and fraud," added London. "That was a judicial outcome that remains highly controversial. But in the course of the trial, a set of admissions of fact were placed on record and these became the basis for the HPCSA disciplinary hearing against Dr Basson."

The uncontested evidence

"It was known that Dr Basson co-ordinated the production of large quantities of illegal psychoactive substances; that he was involved in equipping mortars with teargas for use against Angolan government soldiers; that he provided South African Defence Force (SADF) operatives with disorienting substances to facilitate illegal kidnapping; and that he made available cyanide capsules to SADF soldiers so that they could commit suicide to avoid revealing information under torture," said London.

The HPCSA's scope was limited to those issues that were confirmed as fact during the criminal trial, and did not take into account other allegations. London added that the latter remained on record, but were untested in a court of law.

"However, Basson is on record during an interview for a documentary film as seeming to confirm that Project Coast did, in fact, work on an anti-fertility vaccine that could be administered to black women without their knowledge," London noted.

Medical ethics always apply

Basson's defence rested on nine arguments, each of which was systematically rejected by the HPCSA, said London.

These arguments included that Basson was simply acting under military orders, and that the medical ethics of the 1980s were different to the medical ethics of today.

Regarding the first argument, the HPCSA held that doctors responsible as individuals for their actions, that medical ethics required independence of thinking from medical doctors, and that a doctor cannot simply rely on a military order to escape the consequences of his/her actions.

The second argument was countered by the notion that, while the council acknowledged that the field of medical ethics was not as prominent then as it are today, the principles of 'putting the patient first' applied universally. Further, no doctor could claim ignorance of the expected professional behaviour of a medical doctor.

Importantly, ethical guidelines sometimes superceded laws, reminded Dr Janet Giddy, a family physician and UCT alumnus.

"Sometimes you need to make choices and do things that are against the law, which is what happened during the apartheid days, that may follow your conscience of ethics," said Giddy. "So, there's ethics, morals and legal [issues to take into account]. If you make certain choices that are against the law, there are certain consequences, and you have to be prepared for that."

The military conscription law under apartheid was one case in point, she said.

Giddy also related the struggle of Professor Frances Ames to see that justice was done after the death of Steve Biko as a result of medical negligence by two state doctors who allowed his transport to a military hospital in spite of a head injury sustained as a result of police beatings whilst in detention in 1987.

Ames risked her career as a medical professional by applying for a supreme court order for a full inquiry into the case. She was eventually successful, but risked her career and livelihood in the process. Ames, a single mother at the time, put her own house on mortgage to pay the legal fees.

Transparency is crucial

London called for transparency in the medical practice.

"One of the biggest reasons health professionals become involved in unethical practices is because it happens behind closed doors and is hidden from public scrutiny and peer review," argued London.

He added that it took courage from the panel of "peers" to made the final judgement on Basson and find him guilty of unprofessional conduct.

"It's natural that professionals will feel uncomfortable in disciplining a colleague ' but that often leads to the problem of closing ranks."

Nonetheless, it is possible to resist that pressure to protect peers: "...if you are committed to the ethical requirements of your profession and you are supported in doing so by the institutions of your profession", said London.

Story by Yusuf Omar. Image by Raymond Botha.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.