March of the MOOCs: UCT in the digital era

18 March 2014 | Story by Newsroom

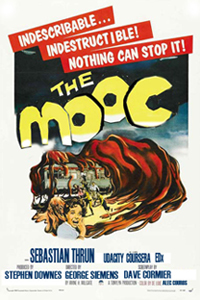

It was a light moment during the panel discussion at UCT's Teaching and Learning Conference late last year: a scene from a horror movie, showing Earthlings fleeing an indestructible, amorphous mass: a MOOC. A similar visual (from Tales from the Planet of Terror) was shown at a free lunchtime lecture on MOOCs at this year's Summer School.

Both pictures underscored an uncomfortable truth: the MOOC (massive open online course) is the lightning rod of educational changes in the digital age, propelling traditional universities like UCT (its staff and its students) into what commerce dean and conference panellist Prof Don Ross describes as an era of "profound uncertainty".

"Our response is defensive, as is right in times of uncertainty: keep your options open, don't commit too early, and protect your human capital."

The 2013 panel discussion on the future of online education at UCT, chaired by Dr Jeff Jawitz, capped a day jostling with 40 parallel sessions on teaching and learning. Much of it had to do with technology and teaching. And this year's Summer School session showed it's not just the young 'uns who're keen to go digital; senior students are also eager to understand how digital will shape their own life-long learning.

One staffer said her mother, a serial Summer Schooler, didn't attend this year's programme. Instead, she enrolled in a MOOC: a digital course on forensic medicine offered by Southampton University.

Clearly, there's much excitement about online learning - but also plenty of uncertainty.

Over 700 000 South African students qualified to enter higher education this year. Some 40% of first-year students drop out in their first year. And only 5% of black African youth in this cohort succeed in higher education.

Are MOOCs the answer?

MOOCs have brought online education into the mainstream as knowledge and information are being democratised in ways we could not have imagined 20 years ago; particularly in Africa, where there's growing connectivity to the world's online education providers.

Attracted by the lure of new markets, Ivy League universities like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have gone out hard.

MIT and Harvard have created their own MOOC platform and provider to attract a new group of students that are not their traditional students, while Yale, Stanford and others have also created a new company and platform. Because these offerings are open (the second 'O' in 'MOOC'), there is no barrier to entry - anyone can take these courses.

Venture capitalists have been even quicker to respond to this potentially lucrative opportunity. In the global market, seven of out the 10 major online education providers are for-profit organisations, says Assoc Prof Laura Czerniewicz of the Centre for Higher Education Development, and director of OpenUCT. (Czerniewicz delivered the Summer School course, and was a panellist at the Teaching and Learning Conference.)

"What has happened is that through MOOCs and through the participation of institutions like Harvard and Yale online, distance education has become legitimatised for traditional residential universities, putting it on the radar of universities like UCT.

"What we're also witnessing," adds Czerniewicz, "is the entree of a dynamic with new players in the online education arena, like Google and publishing company Pearson, representing a reconfiguration of the educational 'space'.

"It makes us feel uncomfortable. We're asking, what's this got to do with us? Like the frog in hot water, by the time we are ready to react, it may be too late."

Brave new world

There's little consensus on how this brave new world should be traversed - and annexed.

"How will online education transform our business? We have no idea," says Ross. "We're dealing with radical levels of uncertainty. There are too many drivers of this change that we can't control."

In the 21st century, learning and education will be driven by macroeconomics and by the global and regional economies, and will be aligned with the skills and labour needs of commerce and industry, says Ross.

Conference panellist (and deputy dean of undergraduate education in the Faculty of Engineering & the Built Environment) Assoc Prof Brandon Collier-Reed expanded on this notion.

"Residential life is very important to the undergraduate cohort. Studies have shown that it is younger students, black students, and students who have lower grade-point averages who suffer reduced performance in fully online courses."

And then there's another cold hard fact for South African educators: research in the US, shared at the Summer School lecture, shows that it's the self-regulated, educated students who are succeeding in the world of MOOCs.

"Only at postgraduate level is there space for a fully online, distance education version of our offerings," explains Collier-Reed.

"It doesn't make sense in South Africa to have UCT offering fully online undergraduate courses. It's against the social contract we make with our students to do what's in their best interest. We need a blended learning environment that includes online resources and open education resources."

It's a question of balancing student needs and UCT's own research and postgraduate niche.

The commerce faculty has come at it from another angle, investing in capacity for online education through an exclusive partnership with online educator GetSmarter. This provides a valuable platform for market research.

Czerniewicz cautions against a one-size-fits-all approach, distinguishing three models of teaching and learning:

- blended learning, a combination of online and residential within and across courses;

- online learning, where whole courses are presented via the web; and

- distance education, where students and academics are separated physically and may or may not be online.

"We should be researching and selecting what works for UCT."

One scenario sees universities shaking down into different kinds of institutions - elite and mass. Another scenario suggests that public universities would be doing the research and teaching would move into the private sector.

"This would be at odds with UCT's strategy to balance success and access, and teaching and research," says Czerniewicz.

"We don't want other organisations to take over our teaching function, but we do need to design for disaggregation."

Blended learning

The model proposed was one of campus-based, blended learning for undergraduates (the 'UCT experience', where student support services are available), and the inclusion of fully online postgraduate study.

"There's consensus that dual-mode universities are very different from traditional universities. What this will need is greater planning and integration, and a better service culture. The extreme flexibility of technology will say where we go," says Ross. "We need to be ready for a future; our response partly technical and substantially intellectual."

As Czerniewicz observes: "Blended learning will be the norm. It's not a matter of 'if'. We just have to decide 'how'. Maybe MOOCs are not the beasts at the gate after all."

Story by Helen Swingler. Main image by Giulia Forsythe on Flickr. Other image of Assoc Prof Laura Czerniewicz speaking at 2013 Teaching and Learning Conference by Raymond Botha.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.