UCT engineers help make medical history

27 February 2012 UCT engineers have helped a local clinician - and Mother Nature - in two groundbreaking surgeries repairing entire cleft palates. The work has earned the team Popular Mechanics' award for South Africa's Inventor of the Year

UCT engineers have helped a local clinician - and Mother Nature - in two groundbreaking surgeries repairing entire cleft palates. The work has earned the team Popular Mechanics' award for South Africa's Inventor of the Year

If nature abhors a vacuum, it sometimes needs a helping hand to fill the gaps.

A push - or a tug, to be more exact - is exactly what a team made up of UCT mechanical engineer Dr George Vicatos, his MSc student James Boonzaier and maxillo-facial oral surgeon Dr Rushdi Hendricks offered Mother Nature. In benchmarking pieces of surgery - probably world firsts - last year, they harnessed some established surgical principles and fine metalwork to rebuild a patient's entire missing palate, or cleft palate.

A cleft palate, basically, is a hole where the roof of the mouth should be. This typically occurs when the body's natural structures don't fuse as they should before birth. Usually these clefts are filled by surgery soon after birth or in early childhood.

But the problem also remains common among adults. Such as when cancerous palates are removed in later life, for example.

Cleft palates visit a string of medical conditions on patients. Because there's no wall to separate the oral cavity from the nasal cavity (a condition known as velopharyngeal inadequacy), patients suffer from speech difficulties, and they have to bear the indignity of food passing from the mouth into the nasal passage, and the embarrassment of nasal fluids slipping into the mouth.

Remedies in adults include the use of a prosthetic known as a palatal obturator, which is more or less a souped-up denture. Another option is a bone graft, which involves replacing the palate with bone removed from elsewhere.

But these are unsatisfying, for different reasons. The obturator is still messy, and the bone used in grafting doesn't allow for teeth implants, for example.

For some years, however, Hendricks and surgeons around the world have been applying a technique known as distraction osteogenesis to regenerate bone in the lower jaw.

Distraction osteogenesis was the brainchild of Russian surgeon Gavriil Ilizarov, who in the 1950s developed the technique to grow missing bone, typically in the leg. Applying the law of tension-stress, he found that if he carefully severed (or distracted) the bone and, a little tug at a time, pulled it apart, new bone and tissue would fill the in-between space.

"The body does the work," Hendricks explains.

But the principle only works if the membrane lining the bone, known as the periosteum, is kept intact. That periosteum contains life-giving progenitor cells that, like stem cells, can direct the body to grow missing bone and tissue where needed.

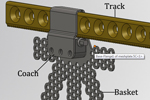

In his work with distraction osteogenesis, Hendricks borrowed from the design of a 'plate-guided distractor' developed by American surgeon Alan Herford. Think of the contraption as a train coach guided by a track, he explains. The distractor, which clamps onto a chunk of severed bone or 'transport disk' via a mesh 'basket', is the coach; the 'fixation plate', a metal plate commonly used in orthopaedic surgery, is the track.

Finally, a strategically placed screw allows the surgeons to move the distractor along the plate, pulling at the severed bone bit by bit.

But while Herford succeeded in growing new bone and soft tissue in the lower jaw or mandible, other surgeons could not do the same for the upper jaw or maxilla because of its peculiar anatomical constraints. When they did, but could only work in a straight line of up to 20mm.

But now Hendricks has pushed that boundary to 40 mm and beyond. That requires the plate to negotiate some tricky corners and bends, or a "curvilinear vector".

"The problem is, how do you stretch bone and tissue around a curve?" he asks, spelling out the engineering hiccup.

While other engineers balked, Vicatos, of UCT's Department of Mechanical Engineering, gladly took up the challenge. He eventually turned it into a project for Boonzaier, who designed the contraption, now patented by UCT. (Boonzaier's involvement was funded by the Medical Research Council.)

In operations over late 2011, Hendricks implanted the team's distractor into two patients. In the first they filled a gap of 40mm, in the second, 80mm. The second surgery required a few ergonomic modifications to fit the demands of the patient's missing palate, and to replace three-quarters of the upper jaw.

Other than the apparatus itself, Hendricks had a post-operation trick up his sleeve as well. While distraction is usually done at a rate of 1mm a day in adults and 2mm in children, he'd decided on 1.5mm per day in his patient. That, he explains, would allow for the growth of both the soft and hard bone and the tissue that make up the palate.

"It's more fantastic than I could have imagined," said a clearly impressed Boonzaier when he first saw the new palate forming.

Others have been equally awestruck. In late 2011, sci-tech magazine Popular Mechanics named the team South Africa's Inventor of the Year for the design. More operations are lined up. And more tweaks to the design.

"We haven't just stopped working on the device after the first operation - we're continuously improving it," reports Vicatos.

The distractor is not going to be a luxury item only, the team promises. While they're still costing the entire exercise, they're confident that both the surgery and the gadget will suit the pockets of both medical schemes and state hospitals.

And they'll make sure the gadget will be produced by a local company. Which suggests that South Africa could soon be the talk of the maxillo-facial surgery world.

|

|

|

| The plan: The team's pre-surgery mock-up of how the distractor would fit onto the patient's jaw. (Images provided by Dr George Vicatos and Dr Rushdi Hendricks.) | Metal work: The team's revised, second design of the distractor. | Turning the screws: After the operation (from left) Dr Rushdi Hendricks, Dr George Vicatos and James Boonzaier move the distractor's 'coach' along the track. |

|

||

| Then and now: The patient's cleft palate (left) and full closure (right) a month later. | ||

YouTube video:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.