Seasons blow hot and cold

16 May 2005

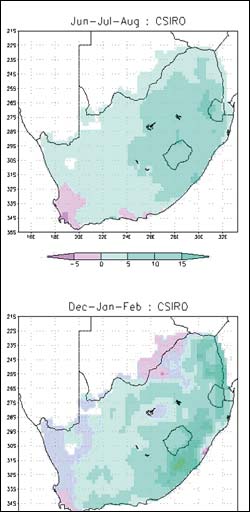

These images show one projected possible change in mean monthly precipitation total (mm) for the end of this century, ie. the change in rainfall between now and then.

Remember the old line that winter in Cape Town was much like a baby - wet and windy? Ah, the good old days. And how quickly things can change.

The Western Cape has just come out of two unseasonably dry winters and yet another in a string of searing summers. And despite some promising cloud cover and encouraging television forecasts, the rain just won't fall even as winter closes in.

But two dry winters and a couple of scorching summers don't a pattern make, cautions climatologist Professor Bruce Hewitson of the Climate Systems Analysis Group (CSAG), a research unit in UCT's Department of Environmental and Geographical Science. "We do have natural variability," he says. And the province did, after all, suffer a three-year dry spell in the 1970s, and then quickly recovered.

There are enough signs, though, that the Western Cape's typical winter-rainfall climate is taking a long-run turn for the worse. First of all, it is getting warmer. That's not too surprising given what's happening around the rest of the planet, with global warming sparking a general rise in temperatures.

Hewitson and others believe that global warming also brings more extreme events, like floods and droughts. "Global warming adds energy to the Earth and atmosphere," he said in a recent newspaper interview, "and with more energy, weather events can be more intense."

In addition, there also seems to be a trend towards drier, early winters in the Western Cape, with rain falling in more concentrated spurts rather than over protracted periods. "Which means it's less effective in contributing to water storage," says Peter Johnston, also of CSAG.

Locals are starting to feel the pinch as water resources dry up. Recently, Western Cape farmers had to be bailed out by the local government as their crops wilted in the drought.

In the face of this threat, the provincial government - and maybe even the national one - needs to draw a long-term water management plan.

"The problem is that we design our societies around a 'normal' climate," says Hewitson. "But when you change that climate in either direction - be it wetter or drier - you stretch the capacity of the systems you designed."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.