Hope for children with fetal alcohol syndrome

04 April 2005

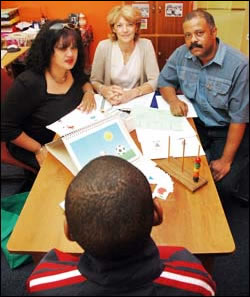

Classy work: (From left) As part of an international collaboration, clinical psychologist Bernice Castle, principal investigator Dr Colleen Adnams and psychometrist Sean September are doing a study on learning difficulties among children with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). In this new project, the researchers will be working with nine- and ten-year olds from town and farm schools in Wellington and surrounding regions.

Researchers from UCT and their counterparts at the Universities of New Mexico and Stellenbosch are working on a novel research programme to provide practical interventions to assist the development of children with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS).

Called the Intervention Study, and part of the Collaborative Initiative on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (CIFASD), it is funded by the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse. The project works with approximately 100 children, aged between nine and 10 years, from town and farm schools in the Wellington region. The intervention phase of the study will run over an 18-month period.

"We are taking children that we know from previous studies have been exposed to alcohol prenatally, and comparing two classroom interventions and a parent intervention in a standardised manner," explained Dr Colleen Adnams who heads developmental services at the Red Cross Children's Hospital and the Division of Child Development and Neurosciences in the School of Child and Adolescent Health. Based at the school's Child Health Unit, she is also the project's South African principal investigator.

"Working at a cognitive level in one classroom intervention (Cognitive Control Therapy), we try to teach the children how to think about learning. This happens spontaneously in most children, but children with FAS don't develop the building blocks to move forward. Through a systematic process involving structured games, toys, play and learning activities, we teach the children to recognise, process and use information."

Children with FAS also experience marked delays (18 months and more) in language and literacy development. For this reason the second classroom intervention works with prelinguistic skills, using basic sounds and language, before progressing to the literacy component of the intervention.

"Both interventions aim to influence a child's ability to benefit from formal education in the areas of thinking and literacy," Adnams adds. "And we hope to show that the interventions are effective and the extent to which they have facilitated improvements."

Understanding the marked influence of a child's home environment and the emotional link to learning, the researchers have also put in place a parenting intervention. A school psychologist assists parents with various parenting skills and issues surrounding learning and behaviour.

"Many of the parents have not had the benefit of much formal education and they don't know how to support their children's learning process. We would like to examine how their influence is carried over to the children."

For over 30 years, research on FAS has tried to answer questions at many levels. These include determining the size of the problem and the effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on children in terms of learning, behaviour and growth.

Previous research on FAS in Wellington has determined the problem is huge, and although children with FAS have learning and behaviour problems, small pilot studies conducted by the team showed they do respond to interventions.

Children receiving the interventions are taken out of their classrooms once or twice a week for a total of one hour's intervention. According to Adnams, this is not perfect but it is sustainable.

"This is not nearly enough time; it is less than the gold standard, but we needed to set a realistic method so that if the interventions work, we will be able to implement them in the prevailing circumstances."

And realistic this type of research clearly is.

Applying science and research to a human system involves hands-on work and many everyday situations are completely beyond the researchers' control.

"There is no glamour in this work," says an impassioned Adnams. "Most of the children are from impoverished backgrounds and don't even have breakfast in the morning. We have to feed them before we can begin the interventions so that we can rule out hunger as a reason for not improving. It's heartbreaking and humbling to see children choosing not to eat but rather to take the food home to their families.

"When you're conducting research in a lab you can control most things, but when you work with humans, you can't. You constantly need to be aware of the realities and take them into account in your planning."

This is where clinical psychologist Bernice Castle comes into the equation. As the programme's project coordinator, Castle supports Adnams in the day-to-day running of the research activities and pulls the team together.

Castle affirmed: "The challenge of undertaking community-based research, where the community is a partner in the research, is that we have to go very slowly and set clear terms of reference before any work is undertaken. In this way, we ensure that we get buy-in from the community.

"We have to think about the community we are working with and communicate with them at all levels to ensure what we are doing is a success. We also encourage them to give us feedback through various structures."

In addition to the interventions, the research will also involve a battery of tests conducted over several international sites to find a key neurobehavioural profile of FAS. This will either support or dismiss the researchers' hypothesis that FAS children have specific difficulty with abstract tasks and higher problem-solving abilities.

The neuropsychological tests on about 200 children, aged between nine and 14, will, however, also highlight these children's strengths. The team will then be able to exploit these by making sure their interventions take them into account and use them to build up the weaker areas.

The cause of FAS is alcohol abuse during pregnancy, and it is 100% preventable. It has been around since biblical times but was first officially described in medical literature in 1973. It is currently a leading cause of learning problems and intellectual disability in western societies, and occurs among people of all social and economic backgrounds.

The effects associated with FAS include facial abnormalities (small eyes and underdevelopment of the upper lip), growth disturbances (small head circumference, small size and weight), neurodevelopmental problems (learning, behaviour difficulties and intellectual disabilities) and other associated problems that may, but do not always occur, including heart defects and poor muscle tone.

"These children have small brains and are wired differently," noted Adnams. "We can't cure the effects of alcohol on their development but we can minimise the impact and prevent further problems and secondary disabilities.

"It's obvious that the first prize is to prevent FAS in the first place, but given that it has been around for a long time we are not readily going to be able to change human behaviour. Children with disabilities are always written-off. We hope to give them a chance by getting them to function optimally. It's a personal passion for all involved."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.