Time to use urban transport as a vehicle for integration

22 November 2004

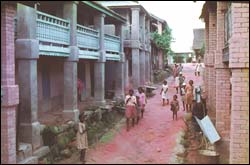

Ambalavo, Madagascar: The street as a multi-functional space and as a means of community building.

The first photograph in Professors Dave Dewar and Fabio Todeschini's new book is a street scene dubbed "positive space". The buildings face up across a narrow street, which leads to a village square; children and women walk abreast, in groups. It is a view of a part of a small settlement in Madagascar and there is not a car in sight.

The street is a communal space, a meeting place, a place for play, or as the authors put it: "the street is a builder of community, social needs taking precedence, not engineering efficiency." The comment provides a useful entreé to their book, Rethinking Urban Transport after Modernism: Lessons from South Africa, released in October and published by Ashgate Publishing Limited, part of its Transport and Mobility Series.

Indeed, the seminal difference between "street" and "road" is a recurring theme of the book, both textually and through pictorial "essays": the latter mainly drawn from Todeschini's photographs of many settlements in Africa, Europe and elsewhere, variously taken since the early 1960s.

The volume is a product of three to four years' joint work as part of the activities of the Transportation Research Group in the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, aimed at "starting a conversation" among professionals in the built environment.

The authors reflect on society's obsession with technology and, particularly, the car and its platform - the roads, highways and flyways that cut swathes through communities and influences the quality of the urban environment. They point to the fatal flaw of modernist town planning: the separation of the functions of "live, play, work, move", as set out in the Athens Charter of the International Congress of Modern Architecture of 1933.

"This elemental functional separation, and the role of highways as space-bridgers, is fundamental to modernist town planning, and the ideology of apartheid found in this construct the very means it sought to give effect to its policies: apartheid grotesquely exaggerated modernist town planning," they add. "The real issue now is how to use transport as a vehicle for integration."

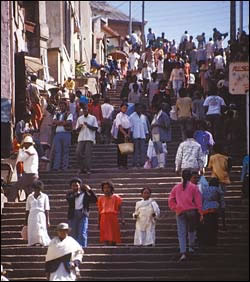

Antanarvio byway.

While the book uses South Africa as a case study, its lessons apply to all cities and particularly to settlements in the developing world, which are characterised by rapid growth and very high levels of poverty.

"The assumptions underlying the modernist approach to urban movement, still deeply entrenched in most countries, are entirely inappropriate," the authors contend.

"The country's Development Facilitation Act, for example, required all land decisions to contribute to making settlements more equitable, compact, integrated, mixed-use and sustainable, but these characteristics are almost precisely the opposite of the urban outcome that resulted from the paradigms of modernism and apartheid."

In fact most transportation plans are still reactive to existing demands, with major transportation decisions taken in silos.

"In many cases they seek to increase mobility, rather than grappling with the difficult questions of how to increase accessibility and convenience for the majority of people and how to reduce aggregate distances travelled."

Consider that in 1904 Cape Town's population was 265 881, the built-up area a mere 23sq km, with a density of 115 people/ha. By 2000 the city's population had swelled to 3 000 000, the built up area is spread over 774sq km with a density of 39 people/ha, a third of what it was a hundred years ago. Inevitably, Cape Town is inconvenient for the vast majority as a consequence.

Given their arguments, it's hard to understand why private cars (owned by 18% of the population) have taken such precedence in the built landscape, bleeding development and urban sprawl into the valuable tracts of agricultural land on the peripheries of cities like Cape Town. And more pertinently, why has there been so little change since the 1950-60s, when modernist planning was at its height?

"Even current transport legislative and policy documents, which are specific about national and regional transportation, prescribe little on urban transportation and how it should be used to achieve required urban outcomes: there is little about the role of movement in settlement-making, which is the central planning issue," the authors say.

It's an issue that has received little attention in literature and this is the gap the book hopes to fill.

In Cape Town in the last part of the 19th century trams and private railway services opened up town extensions such as Camps Bay, Wynberg, Milnerton and a number of developments on the Cape Flats.

"The characteristics of the different movement modes created distinctive patterns of development. The growing widespread use of cars enabled development to break away from the locational specificity of the continuous routes and established patterns and processes of sprawl. Development now follows major intra-settlement freeways, promoting urban sprawl and encouraging new development techniques resulting in regional shopping centres, office and theme parks, small business and manufacturing parks, and so on," they write.

But transportation shouldn't dictate settlement patterns, they argue; this should follow the imperatives of the urban whole.

Other statistics they cite reveal another side to the problem; in 1992, 63% of South Africa worked in urban places and travelled over 16km in each direction between home and work, some moving up to 100km over periods ranging from three to four hours.

"Urban settlements are impositionary, out of step with the economic realities of the majority of people and entirely non sustainable." According to the authors, new policy directions set by the South African National Department of Transportation demand radical departures from past practices and urban forms.

"Those policy directions are laudable and necessary: current practices, particularly in relation to public transportation, are entirely non-sustainable. The current situation, if not significantly improved, has the potential to bring larger urban systems in South Africa to a standstill."

But achieving significant improvements, they say, requires a paradigm shift about how urban movement is considered from urban and transportation practitioners and decision-makers alike.

Adopting a cautionary tone, the authors cite recent lessons from Harare, where, in that country's current inflationary context, transport costs are absorbing up to 80% of the household income of the poorest of the poor.

"It is a chilling testimony to the consequences of simply repeating historical practices. The alternative of moving towards sustainable urban and transport options is difficult, confrontational, and exciting, but in the final analysis, unavoidable."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.