A platinum opportunity

27 September 2004

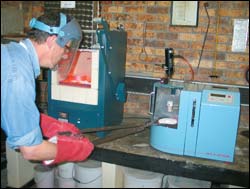

Hot stuff: Dr Duncan Miller at work using the platinum research group's platinum-melting machine, the Hot Platinum Icon 3CS. The precious metal is beyond white hot at this stage, melting at 2

It's not often a start-up project testing new technology finds its way in so public and symbolic an application as Parliament's new mace, redesigned recently to celebrate 10 years of democracy.

Without the mace, an age-old symbol of power and authority, Parliament is not considered properly constituted. Unveiled earlier this month, the new model stands 1.196m tall and weighs almost 10kg, most of that attributable to the gold, precious stones and indigenous woods used in its creation, not to mention the solid platinum rings around the shaft, echoing the neck rings worn by Ndebele women.

Project leader Martin Amman of Oro Africa, who were commissioned to produce the new mace, took an innovative approach and partnered with UCT's Hot Platinum team to manufacture the challenging platinum castings. This gave Associate Professor Candy Lang's team a (platinum?) opportunity to put to work the innovative prototype platinum-casting machine developed in a collaboration between UCT's Centre for Materials Engineering and the electrical engineering departments at the Cape Technikon and UCT.

The latter project is part of a R5.6-million Innovation Fund grant to the team to develop a commercially-viable platinum-melting device to boost the platinum-jewellery manufacturing industry, estimated to be worth well over US$1-billion a year. The team has also been testing new platinum alloys.

South Africa and Russia are the world's foremost platinum producers, but South Africa had been unable to harness any secondary benefit from the precious metal.

Melting platinum may sound ho-hum, but the metal is difficult on two fronts. It's too soft on its own to hold precious stones, needing "beefing up" with the addition of elements like copper and ruthenium. It is also difficult to cast, requiring "more than white hot" temperatures of up to 2

Research teams lead by UCT's Irshad Khan and Professor Jon Tapson designed a toaster-sized prototype first publicised in Monday Paper in November last year. (Vol 22#34). Special features are its compact size, and the fact that it works off the standard domestic power supply, melting 100g of platinum in less time than it takes to boil a kettle.

The average platinum wedding band weighs 5g. This machine can melt up to 500g at a time, using a standard, domestic power supply and plug point. The wide melting range reduces the input metal costs incurred with casting techniques, and also means jewellers don't have to keep large inventory holdings as the items can be cast on demand.

The newly-modified prototype has seen some refinements and goes by the name of the Icon 3CS, manufactured by the Hot Platinum technology company, a spin-off from the Hot Platinum research project. It's about the size of a microwave oven, small enough to fit in a jewellery workshop.

The team, a mixture of postgraduate students, entrepreneurs and academics with expertise in materials, as well as mechanical and electrical engineering, is justifiably chuffed.

"It's been very exciting to see this emerge from a research project," said Lang. "It was quite tricky taking something like this from the laboratory to the marketplace. But it's been a privilege to have worked on a project like this."

The platinum crafting for Parliament's mace was not without its own headaches. Take the 820 platinum beads that had to be cast for the colour white in the national flag depicted on the shaft.

Each platinum bead is 2mm in diameter with a 1mm hole, finicky stuff. The plug was thus an interesting combination of cutting-edge research and age-old beading techniques. (The yellow beads are made of gold and the rest are coloured glass.)

The platinum rings required other moulds, built up from wax using lost-wax casting techniques.

"It's based on the ancient technology of lost-wax casting, first used in Africa, particularly in West Africa, to cast bronzes and brasses 1 000 years ago," Dr Duncan Miller explained. "We're using a modern version of that technology." (Miller, an archaeologist and metallurgist, wears many hats at UCT.)

The team is exceptionally chuffed with their casting precision; the mace, built around an aluminium shaft, fits together and the two main platinum pieces housing the beaded flag glide to fit, with 0.1mm accuracy. They have also been conducting a structured system of tests to stretch the platinum-melting machine to its limit.

Working in the laboratory today, Miller resembles a metal forger of old in a leather apron and tongs, bending over a furnace. He has constructed a mould that includes standard ring shapes and finer, more intricate filigree patterns needed to provide variety in the jewellery-manufacturing process.

Understandably, the mace manufacturing operation was a hush-hush affair down in the UCT platinum laboratory.

"We were the only place that offered the advanced technology in casting, metallurgy and machine, all under one roof," Lang said.

But there is more to look forward to. There is the anticipated launch of the Icon 3CS, bringing a portion of their work to fruition. The Hot Platinum company, lead by managing director Ali Brey, will take the project from here into commercial pastures.

Hopefully, it will sell like hot cakes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.