UCT hurdling great pipped by apartheid

16 August 2004

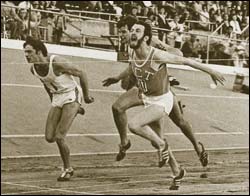

Neck and neck: Assoc Prof Chris Breen (right) winning the first multinational athletics hurdling event in South Africa, 1968. "Whoever got to the first hurdle first would win it." He still holds the UCT 110m hurdles record of 14.1 sec, set in 1971.

It was March 1968 and Chris Breen had whittled his 400m hurdles time to a slender 51:2 seconds, setting a new Western Province record at Coetzenburg. A paltry 0:2 seconds stood between him and an Olympic qualifying time of 51 seconds. A month earlier he had clocked 49:1 sec at an athletics meeting in Worcester.

Then came a devastating blow for Breen. Rated as the second fastest junior in the world at the time, the South African participants learnt they would not attend the Mexico Olympics. The majority of black African states competing had threatened to boycott the games if they did.

Without this lofty target, there seemed little point in continuing, Breen felt.

"It suddenly didn't seem important to get below 51 seconds."

Human and civil rights issues shaped the Mexico games in other ways. The 200m sprint medal ceremony saw United States' Tommie Smith (gold medal) and John Carlos (bronze) bow their heads and raise black-gloved fists, a symbol of the black-power movement. Though the team's management banned them, they had made history. (Despite death threats later, both went on to coach high school track teams and were honoured in 1998 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of their protest.)

But the exclusion was a bitter blow for Breen, the BSc alumnus who went on to become associate professor in the education department. It put a dent in his hopes of becoming a world contender, though he later had a crack at the British Olympic team while studying at Exeter University in the mid-1970s.

The asthmatic child was perhaps an unlikely athlete. But Breen lived for sport. A dayboy at Bishops, he was allowed to take part in the annual sports day "on sufferance".

"I was sick for weeks afterwards," he recalls.

He is not overly keen to relive past glory. It takes some persuasion (several cajoling e-mails) to get him to backtrack this far. He's prouder of his daughter Alison's prowess as a former top basketball player. Alison had the makings of an Olympics contender in the sport, but stopped to pursue other interests.

Tall and rangy in his youth, Breen excelled as a runner and high jumper. But neither event particularly excited him. Not like hurdles, particularly the 400m event. Here his height perfectly augmented his speed and he began to put some real effort into training.

It was a myopic sports coach who told him he'd never make a hurdler, sparking a flinty determination in the youngster.

"This is not something you say to me," Breen comments wryly.

Instead of being gangly and uncoordinated (as his height suggested), Breen's technique was sound.

"You have to hit each hurdle low and flat, almost grazing it with the back of the thigh," he explains. "The lower the better."

Hence the term "timber topping".

He broke a school record and later a triangular record. Then he won the South African under-17 title. In grade 11 came his first taste of bigger things; he competed under-19 in an international against German athletes as a junior in the Western Province athletics team.

Later, the press described him as "among the world's best", and " – one of South Africa's most promising juniors".

He went on to break the great Gert Potgieter's record with 51:8 sec in the 400m. (Potgieter had set three consecutive world records in the late 1950s.) It was at a Western Province championship, in only his second season in the 400m distance, that Breen clocked 51:2 seconds.

In 1968 he won UCT's Sportsman of the Year award and the Landstem Trophy. It was also the year the UCT team of Ted Warren, Lucien Petersen, Simon Perkin (now a master at SACS High) and Breen set up a new South African record for the 1 600m medley relay.

But Breen is not alone. There were others top athletes of that era who were thwarted - Paul Nash, for one, who ran the 100m in 10:1 seconds, only 0:1 second outside the world's best.

Now, in 2004, 12 years after the country's first foray back at the games, Breen is reflective, certainly not remorseful, about a missed platform of opportunity.

"It was the right thing to do," he says of the boycotts. "It put pressure on South Africa [to change]."

When he watched the first live broadcast of the Olympics on TV in 1994, it was at home with his children. The 400m hurdles brought a moment of poignancy, with Breen enthusing and pointing his bemused family to the finer elements of technique ("Look, he's changing legs!").

There will be a feast of viewing this year with South African hurdlers Okkert Cilliers, Llewellyn Herbert and Alwyn Myburg competing in the 400m and Shaun Bownes in the 110m.

Breen says he still dreams of turning up at athletics meetings, fetching the hurdles behind the pavilion at the UCT oval, measuring the distances on the track and then crouching for the starter gun, mentally visualising his onslaught.

"In seven strides you have the first hurdle," he remembers. "You fling yourself at it. It's a suicide mission."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.