UCT remembers icons

09 January 2004

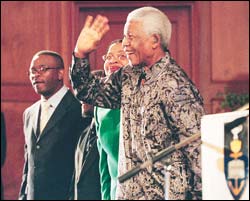

Struggle icon: Former president Nelson Mandela greets the throng in Jameson Hall, with chancellor Graça Machel at his shoulder. Mandela has made a handsome pledge to the Chancellor's Challenge 175 campaign.

There will be many highlights in the annals of UCT's 175th year. Sadly, 2004 has also seen the passing of South African icons: Dr Beyers Naudé and Ray Alexander Simons. And in his Steve Biko Memorial Lecture address on September 10, former president Nelson Mandela remembered two more stalwarts: Steve Biko and Oliver Tambo. Monday Paper compiled these extracts.

It was to a packed Jameson Hall, with a televised screening in the adjacent Molly Blackburn Hall, that Mandela conducted his tribute to Steve Biko, ruing the fact that he, like others, had to watch Biko's influence on the country's political landscape from the confines of prison.

"And as we now increasingly speak of and work for an African Renaissance, the life, work, words, thoughts and example of Steve Biko assume a relevance and resonance as strong as in the time that he lived," Mandela said. "His revolution had a simple but overwhelmingly powerful dimension in which it played itself out - that of radically changing the consciousness of people. The African Renaissance calls for and is situated in exactly such a fundamental change of consciousness: consciousness of ourselves, our place in the world, our capacity to shape history, and our relationship with each other and the rest of humanity."

Biko's consciousness was a key concept in his political approach and vocabulary - at the essence of his strategic brilliance and understanding, Mandela added.

"That intervention came at a time when the political pulse of our people had been rendered faint by banning, imprisonment, exile, murder and banishment. Repression had swept the country clear of all visible organisation of the people."

And though he lauded the country's progress and transformation, Mandela was concerned about the country's "RDP of the soul", since the advent of democracy.

"The values of human solidarity that once drove our quest for a humane society seem to have been replaced, or are being threatened by a crass materialism and pursuit of social goals and of instant gratification. One of the challenges of our time, without being pietistic or moralistic, is to reinstil in the consciousness of our people that sense of human solidarity, of being in the world for one another and because of and through others."

In his address, Mandela also saluted Oliver Tambo, highlighting his "possibly unique" leadership during the hardships of political exile on foreign soil.

"The history of South Africa could have been so vastly different if Oliver Tambo had not provided the leadership he did at the time and in the circumstances," Mandela said. "The struggle against apartheid became one of the foremost moral struggles of the twentieth century."

In its own commemoration of Biko last week, the health sciences faculty hosted a talk by Wits University's Professor Yosuf Veriava. Veriava was one of the doctors who successfully put pressure on the South African Medical and Dental Council (SAMDC) in the mid-1980s, via the Supreme Court, to launch new hearings into the conduct of the two medical doctors who treated Biko after he was tortured by police.

The mistreatment of prisoners remains a bane of international society, Veriava told Monday Paper. But the issue is bigger than just the care of those who are incarcerated or tortured, he said.

"The issue is about a doctor-patient relationship and how we act, not only when our patients are prisoners, but also when they are disempowered people, people who are very poor and have no-one to stand up for them. The attitude of doctors at present is variable. There are some who do the job properly, but there are many who don't treat these patients and who don't develop doctor-patient relationships that are sound."

The talk was the first event to be financed by the faculty's Steve Biko Fund, money raised by UCT doctors in the 1980s to fund the court case against the SAMDC.

In 1983, when the late Dr Beyers Naudé received an honorary Doctor of Literature from UCT, he was serving a second term as a banned person. He and his wife were given special permission to come to Cape Town and to stay at Glenara. However, he was not allowed to speak at the ceremony. The vice-chancellor at the time, Dr Stuart Saunders, decided to speak on his behalf.

Saunders recalls using the framework of a dream to elucidate the speeches of the *four honorary graduates on the day.

"In my fourth dream Dr Naudé was addressing his congregation. He spoke of man's understanding of God, faith and compassion, of forgiveness and reconciliation, of the importance of one's love of one's fellow man and of the dangers of bigotry and ideology.

"He spoke as a man of God who had turned his back on ideas of racial exclusiveness and had seen so clearly the dangers of apartheid for the Afrikaner people - his own people - as a Christian community, to say nothing of the dangers apartheid held for the rest of South Africa. On a campus such as UCT's, students of diverse cultural and other backgrounds should grow together, should exchange ideas and debate the fundamental problems of life and society."

"When I awoke, I wondered why some would not let Dr Naudé speak. What could be so dangerous in the spoken or written word of such a man? And then it came to me; someone, somewhere, was afraid of ideas, afraid that the fatal flaws in our society might be exposed with such force and eloquence that the folly of pursuing them would become obvious to all.

Saunders told that gathering that the aftermath of the "dream" had not left him discouraged.

"On the contrary, I was exhilarated, because as long as South Africa produced men like the four distinguished honorary graduates, there was hope for us all."

Ray Alexander Simons, who married Jack Simons (he received an honorary Doctor of Laws from UCT in 1994), a former African studies lecturer at UCT, was a champion of the working class and a fierce campaigner for women's rights. Earlier this year the stalwart of the ANC, the South African Communist Party and the trade union movement was awarded Isithwalandwe-Searapankwe, the ANC's highest honour, for her dedication to the cause of freedom and democracy.

She organised workers in many different trades, but her name became synonymous with the Food and Canning Workers Union (FCWU), founded in 1941. In the 1950s, the FCWU played a leading role in the South African Congress of Trade Unions.

In 1953 she was served with the first of a series of banning orders. She and her husband went into exile in 1963, travelling to Zambia. They remained in exile for 25 years but were among the first exiles to return in 1990. Her daughters Mary Simons, senior lecturer (political studies) and Tanya Barben, senior librarian (Rare Book and Special Collections), both work at UCT.

*The other three were Richard Sonnenberg (Doctor of Economic Sciences), Erwin Spiro (Doctor of Laws) and Samson Mbizo Guma (Doctor of Literature).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.