DIY insulation solution for low-cost housing

24 November 2003

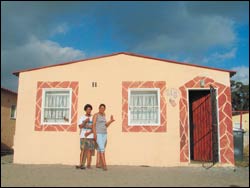

Home improvements: Agnes Kannemeyer and Rachel Jacobs outside their subsidy house in Greenlands, Bellville South. A UCT collaboration is investigating new insulation materials for such homes.

Anything from discarded Liquifruit boxes to plastic bottle tops and post-industrial wood fibre used inside disposable nappies could be the key to improving the quality of life of people who live in the government's "subsidy" houses. An interdisciplinary collaboration between the Environmental Evaluation Unit and the Centre for Materials Engineering at UCT is investigating the possibilities.

Call them RDP houses, "hophuisies", or simply "subsidy" housing, many people who have moved from shacks into their new brick-and-mortar homes after 1994 have found themselves living under less-than-ideal circumstances.

This is because, apart from being tiny, the basic government subsidy makes it difficult to afford ceilings or insulation. This, in turn, causes condensation problems in winter, particularly where there is overcrowding. The attendant health implications are that moulds form on the walls that can cause respiratory diseases. In summer, the heat is unbearable.

Hence the establishment of a collaborative research project initiated by the Environmental Evaluation Unit (EEU) in the Environmental and Geographical Science Department. It was conceptualised by development consultant Ilne-Mari Hofmeyer who has since passed away, in partnership with EEU and submitted together with City of Cape Town for funding from the Provincial Housing Department.

Known as the "DIY-Home Insulation Kit" project, the aim is to come up with creative solutions that are both environmentally friendly, and have the potential for job creation in an area such as Khayelitsha.

"It's complex but interesting," says project leader Sandra Rippon, an architect by training who will graduate with an MPhil in environmental management next month. Rippon, who works part-time at the EEU, was asked to take on the project that had been approved but needed a champion.

A key partner at UCT is Dr Kashif Marcus, from the Centre for Materials Engineering in the Mechanical Engineering Department, who is working on product research and development and testing of prototypes.

Marcus explains: "The idea is to find a two-in-one solution, with the insulating material sandwiched into an all-in-one ceiling board which is easy to install, as well as meeting a range of criteria.

"It is quite exciting that there is a lot of potential in the plastic waste stream. We have been experimenting with plastic packaging, such as bottles and tops, grinding them down and reconstituting them into suitable insulating materials.

"What we have found is that the thermal properties are comparable to existing materials currently being sold on the open market. Now that we know this has good insulating properties, we need to modify the structure so that it can meet the quite stringent criteria laid down by the project brief."

These criteria include finding a product that is affordable and therefore commercially viable, while also meeting technical standards of fire, waterproofing and mechanical integrity. In addition, the product must be practical to use, environmentally friendly and be aesthetically acceptable. It must also have the potential to create small enterprises within the community. The focus is on waste materials that would otherwise go unused and contribute to landfill problems.

Another important partner is Stellenbosch University's Wood Science Department, which is investigating biomass materials such as acacia bark from alien clearance programmes and agricultural waste.

Having recognised the problem of insulation, the government is also offering a top-up subsidy of around R1 000 to provide thermal interventions, including ceilings and insulation, for subsidy houses in what is described as the "Southern Cape Condensation Area", including metropolitan Cape Town. Should the development of a prototype be approved, a community-based manufacturer could go into production.

Among the materials up for consideration are cellulose, corrugated cardboard, plastic waste, and tetrapak (Liquifruit boxes). Organic options are acacia species, hemp, water hyacinth and reeds. On the fossil fuel front, options include mixed plastics (such as bottle tops) that can be shredded and reformed, polystyrene packaging, polyester and textile wastes. A promising option is a waste mountain of unused but shop-soiled post-industrial wood fibre that is commonly used in disposable nappies.

Another line of enquiry comes from a tiny NGO in Ladismith in the Little Karoo, where the Ladismith Action Group makes products out of papier maché using recycled cardboard from industry. One of the products they are making is a kind of softboard which could be incorporated into one of the prototypes.

The project team is drawing on expertise provided by a technical advisory group of academics, consultants and NGOs in the design, research and development of the insulation product. Another reference group is being consulted on socio-economic issues. Members of these groups from UCT include Denis van Es (Energy Research Institute), Eugene Visagie (Energy and Development Research Centre), Gita Goven (School of Architecture and Planning), and Dr Harro von Blottnitz (Chemical Engineering).

According to Rippon, the project supports the principles underpinning sustainable development. The insulation is intended to reduce energy-heating costs, increase comfort levels in the home and to be affordable to the lowest income households. The insulation will be designed for local, labour intensive, low technology manufacture and distribution from within the community of Khayelitsha. In addition, insulating homes and reducing the amount of carbon-based heating fuels used supports climate mitigation initiatives.

The project also intends to provide the opportunity - through capital and skills transference - for establishing a potentially sustainable local, labour intensive, and income-generating business.

At this stage, the next step is to find nine or 10 prototypes which will be evaluated before a final few, possibly about three, will be moved on to the development and evaluation phase.

"In the next two months, we will stop developing, and start narrowing and refining what we have," said Rippon. "We hope we can come up with something that is viable. It's a tough challenge to meet all the criteria and make it economically sustainable." For more information, contact Sandra Rippon on 650-2957.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.