Team of electrical engineers galvanise research

25 November 2002

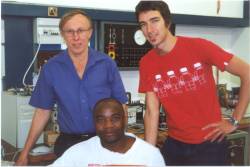

Lighting the future: Some of the members of the team that won this year's Best Research Project with Export Potential, (from left) senior lecturer Michel Malengret, Caxton Magogre and Clinton Slabbert.

THRIP aims to increase local industry's global competitiveness by stimulating the development of technology and appropriately skilled people.

The National Research Foundation (NRF) manages the programme, which is a joint venture between industry, government, research organisations and higher education. According to Malengret, the projects, which involve power electronics and renewable energy, i.e. stand alone converters, grid-connected solar, wind and fuel cell converters have already been exported to England, India, Italy, France and Syria.

“We have a high invertor technology which is on par with world standards. The technology is suitable for converting electricity and matching the load to the supply and doing this as efficiently as possible. The direct result of that is a South African based industry in the field of renewable energy and power electronics,†explains Malengret, adding “and what makes this project great is that it is a good balance between industrialisation and academic work, because you have students giving their input, having hands-on experience, and gaining experience from more senior engineers.â€

The team's many projects are supported by various corporations like Eskom and MLT Drives.

Malengret says that in the past, his team developed converters, which were used by Eskom to supply electricity to over 1000 rural schools in South Africa. The converters were provided to the various contractors that were installing solar panels on at schools and some clinics in remote areas.

“What happens is that the invertor takes electricity from the batteries and converts it to 230 volts AC, as we normally have in the mains of buildings in urban areas.†Malengret explains that their project is making a significant contribution to the South African renewable energy industry. “It could soon also become effective in areas where an Eskom electrical grid already exists because renewable sources of electrical energy can be fed into the national grid and can then be supplied anywhere.

“With a grid-connected invertor you don't just supply your local area with renewable energy but excess energy can be passed to other consumers further a field. We actually put it into a grid so it can supply people further a field.

This is known as distributed generation where electricity can be supplied from local sources and distributed widely, hence offering peak demands of other consumers,†he concludes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Related

‘The queue hasn’t moved’

02 Mar 2026

UK en KAS vier die sokkerleierskap van graduandi

02 Mar 2026

Afrikaans