Fossil discoveries rewrite human history

02 April 2020 | Story and photos Supplied. Read time 5 min.

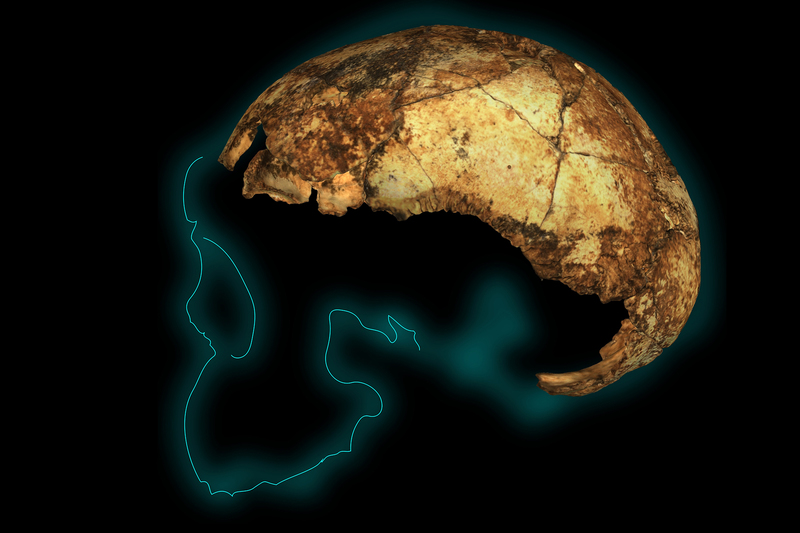

An international team of researchers, including geologists from the University of Cape Town (UCT), has reconstructed – from more than 150 fragments – the earliest known skull of Homo erectus, the first of our ancestors to be nearly human-like in their anatomy and aspects of their behaviour. The two-million-year-old fossil was excavated in the Cradle of Humankind in South Africa over five years.

Published today in Science, the findings are part of an international research excavation in the fossil-rich Drimolen cave system north of Johannesburg.

Dr Robyn Pickering, the director of the Human Evolution Research Institute at UCT, says the age of the skull (dubbed DNH134) shows that H. erectus lived 200 000 to 100 000 years earlier than previously thought.

“This is a very exciting discovery,” says Pickering. “We have struggled for decades to date the South African fossils. But now we have a range of suitable techniques, and it’s possible to push back the first appearance of our earliest ancestors in the Cradle.”

UCT postdoctoral research fellow, Dr Tara Edwards, was part of the geology and dating team who reconstructed how the fossils ended up in the cave and checked that the dating methods were accurate.

“By looking at small pieces of cave rock, also known as speleothem, under the microscope, we can tell that the layers we are dating are pristine and we can trust the ages they produce,” says Edwards.

Re-thinking our family history

“The H. erectus skull we found, likely aged between two and three years old when it died, shows its brain was only slightly smaller than other examples of adult H. erectus,” says lead author Professor Andy Herries of La Trobe University’s Department of Archaeology and History in Australia.

“It samples a part of human evolutionary history when our ancestors were walking fully upright, making stone tools, starting to emigrate out of Africa – but before they had developed large brains.”

Herries says that unlike in the world today, where we are the only human species, two million years ago, our direct ancestor was not alone.

Based on the age estimate for this latest fossilised skull find, we can say that H. erectus likely shared the landscape with two other types of humans in South Africa at that time: species of the Paranthropus and Australopithecus genera. This suggests that the Australopithecus species, A. sediba may not have been the direct ancestor of H. erectus – or us – as previously thought.

Dr Justin Adams, one of the paper’s co-authors from Monash University, Australia, says the discovery raises some intriguing questions about how these three species lived and survived in the landscape.

“One of the questions that interests us is what role changing habitats, resources and the unique biological adaptations of early H. erectus may have played in the eventual extinction of A. sediba in South Africa,” Adams says.

“At UCT, we are passionate about changing the face of research into human evolution in South Africa.”

Co-director of the Drimolen excavation project, University of Johannesburg PhD student Stephanie Baker, says the discovery of the earliest H. erectus marks an incredible milestone for South African fossil heritage. “Not only does the research illustrate the importance of South Africa in the human story, but this project is the first major breakthrough in hominin research with a female, South African director.”

“At UCT, we are passionate about changing the face of research into human evolution in South Africa,” Pickering agrees. “We certainly need more South Africans in leadership roles on projects such as this, but this work is making good progress in that direction.”

- Herries AIR et al. (2020) Contemporaneity of Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and early Homo erectus in S. Africa. Science 368, eaaw7293 https://science.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi/10.1126/science.aaw7293

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Research & innovation