Priceless climate-change data haul from Antarctica

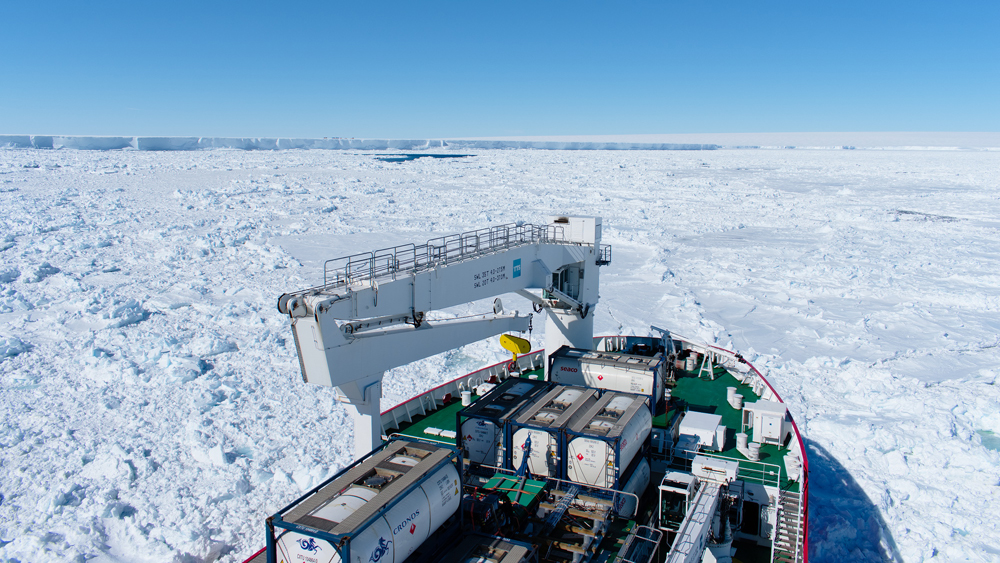

02 April 2019 | Story Helen Swingler. Read time >10 min.The SA Agulhas II in Antarctica – the white continent. Nine UCT oceanography researchers were onboard, part of an international research expedition to the Weddell Sea. Photo Hermann Luyt.

The thousands of seawater, ice and plankton samples brought home by the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) 2019 Weddell Sea Expedition (WSE) research group may take up to five years to analyse and interpret.

But the data yielded by this stockpile will be priceless in understanding changes to the Antarctic ice shelves and their role in climate change.

The nine-member group returned after two months in the Weddell Sea, one of the world’s coldest, remotest and least-studied locations. In his 1950 book The White Continent, historian Thomas R Henry notes: “The Weddell Sea is, according to the testimony of all who have sailed through its berg-filled waters, the most treacherous and dismal region on Earth.”

When it docked in Cape Town on 15 March, the trusty SA Agulhas II had recorded a round trip of over 11 000 km; an “unprecedented” international scientific expedition of 40 world-leading glaciologists, marine biologists, oceanographers and marine archaeologists. Their quest: to research the Weddell Sea’s unique marine environment and the glaciology of the Antarctic ice shelves.

Their first goal was to collect samples from the vicinity of the Larsen C Ice Shelf along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. The second was an ambitious attempt to locate and survey the wreck of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s wooden ship Endurance, built for the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914–1916). The ship was crushed by heavy pack ice and sank in the Weddell Sea in 1915.

Ice shelves and sea ice

The vast collection of samples will contribute massively to understanding the drivers of Antarctic ice-shelf collapse in the wake of climate warming, said UCT’s lead scientist on the expedition Dr Sarah Fawcett.

“The material will also help oceanographers understand the controls on biological nutrient utilisation in the Antarctic Ocean, which is central to understanding its outsized role in setting atmospheric CO2 today and in the past, and in absorbing CO2 in the future,” she said.

The UCT group comprised marine technician Tahlia Henry, postdoctoral researcher Dr Katherine Hutchinson, and postgraduate oceanography students Riesna Audh, Jessica Burger, Raquel Flynn, Hermann Luyt, Kurt Spence and Shantelle Smith.

“I’m extremely excited to work up the results with my students,” Fawcett said.

“It was truly the opportunity of a lifetime for an oceanographer interested in the role of the Southern Ocean and making our planet habitable.”

Endurance wreck site

One of the great drawcards was an opportunity to participate in efforts to locate the Endurance, 3 000 metres below the ice. While the SA Agulhas II’s superior ice-breaking capabilities made it possible to reach the site where the ship is thought to have sunk, the loss of one of the Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV) deployed to survey the sea floor beneath the site halted operations.

After huge public interest, this was a blow. Dr John Shears, polar geographer and WSE leader, said the expedition had included an innovative educational outreach programme, “allowing children from around the world to engage in real time with the expedition and our adventures from the outset”.

Chief scientist and director of Cambridge University’s Scott Polar Research Institute Professor Julian Dowdeswell had said that interest in the Endurance had underscored the importance of the expedition’s scientific and educational work.

Iceberg calving normal – or not

But science was luckier in a region of scant data as the waters near the Larsen C Ice Shelf are typically covered with sea ice year-round. The expedition was fortunate: low sea-ice cover and the SA Agulhas II’s muscle provided valuable access.

Recent, dramatic changes to the Larsen C Ice Shelf make it a fascinating study site. Portions of the greater shelf have collapsed; Larsen A in 1995 and B in 2002. In July 2017, the 5 800 km2 iceberg A68 sheared off Larsen C in one of the largest calving events ever recorded.

“One of our aims was to investigate whether such calving events are being driven by atmospheric and/or oceanic warming, or are part of the natural growth and decay cycle of the ice shelf.”

“One of our aims was to investigate whether such calving events are being driven by atmospheric and/or oceanic warming, or are part of the natural growth and decay cycle of the ice shelf, and to better understand their physical and chemical implications,” said Fawcett.

This has important global consequences. For example, ice-shelf collapse allows land-fast ice from the interior of Antarctica to flow into the sea, driving sea-level rise. In addition to hosting important ice shelves, the Weddell Sea represents a point of origin in the Southern Ocean where water masses form and communicate with the atmosphere.

“These water masses then sink and circulate around the global ocean, which means that the conditions of much of the ocean are set by the various physical, chemical and biological processes happening in the Weddell Sea,” Fawcett explained.

Team expectations – tick the box

The expedition was every polar oceanographer’s dream.

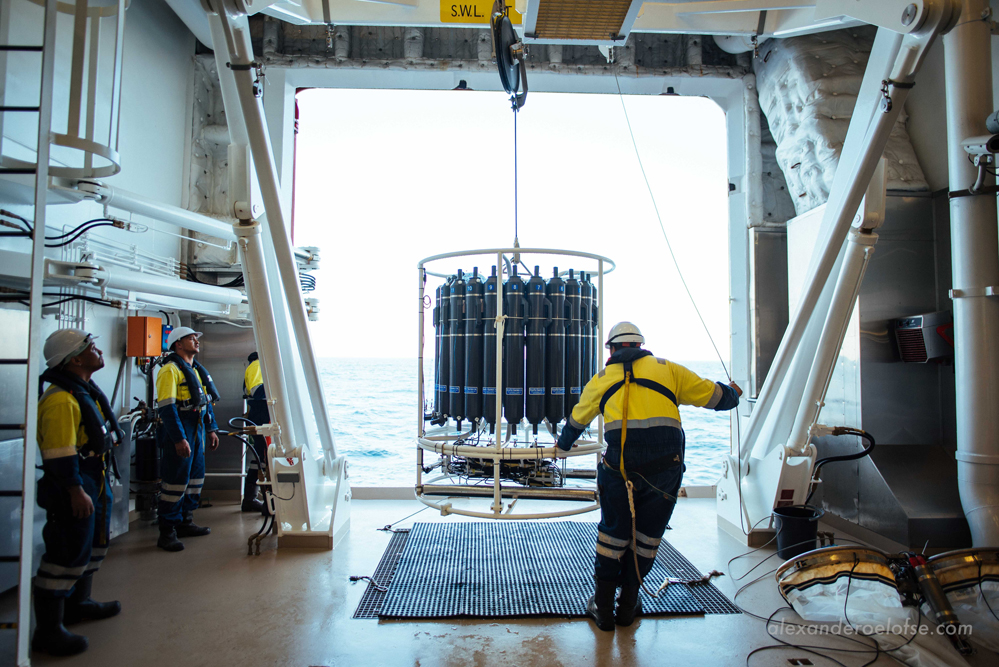

It was Hutchinson’s second Antarctica expedition and she was able to undertake 26 scientific stations within the Weddell Sea.

“My specialisation is understanding the heat and salt content of the ocean and how the ocean is interacting with Larsen C Ice Shelf,” she said.

Audh’s interest was in the physical and biochemical properties of pancake sea-ice in the Antarctic Marginal Ice Zone.

“We were exposed to an incredible opportunity to study a severely under-researched region with state-of-the-art equipment and people who are at the forefront of polar research.”

Luyt added: “Personally, being able to conduct science in such a remote and unstudied region of the Weddell Sea was a huge highlight … seeing the South African contingent come better prepared for the expedition than any of the international groups and performing immaculately when opportunity arose was a point of great pride.”

“As great as the science was, it would have been better still to have found the wreck as well.”

“Multi” group

Working as part a multidisciplinary, multi-institute group was also a privilege.

Hutchinson: “I loved it. I am, by nature, a very curious and enthusiastic person and so I immersed myself in all the different types of science going on and asked a million questions. I found it fascinating and realised so many new avenues for multidisciplinary research and collaboration.”

Flynn: “I learnt so much working with all the different scientists from all over the world. The experience taught me how important collaborations are, both within and across fields, and how fostering those relationships may provide me with opportunities later in my career.”

Audh: “Working with people from different disciplines allowed me to step out of my comfort zone and experience different sciences and techniques – I was exposed to new methods, equipment and ways of thinking.”

“It was exciting learning about Antarctic science from very different fields.”

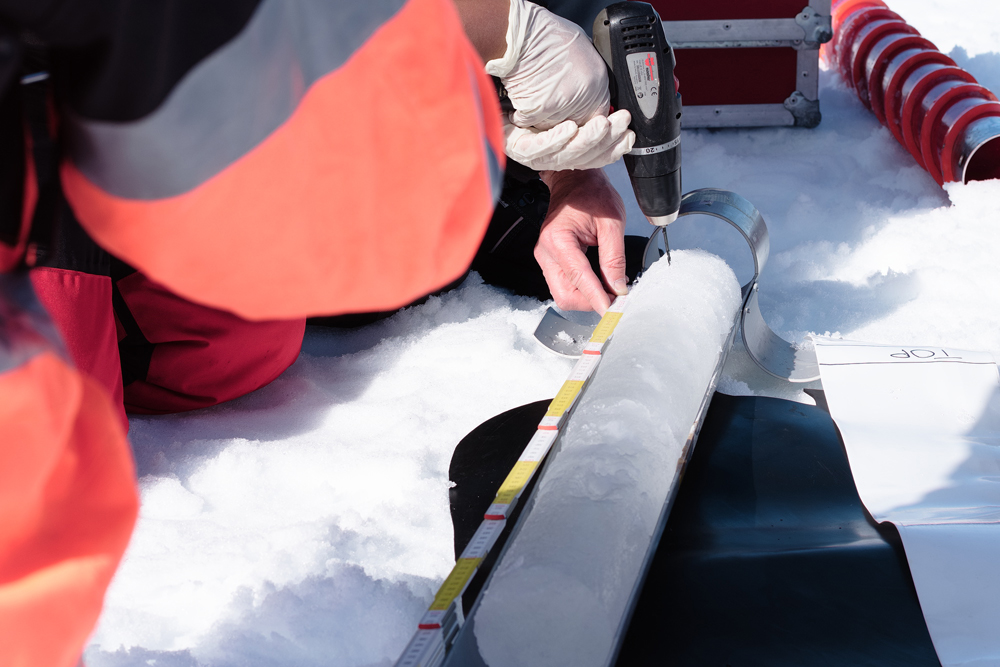

Smith: “It gave me the opportunity to be involved in and to witness scientific methods that I haven’t heard of being done in South Africa. The ability to assist with the processing of sediment cores was incredibly enjoyable since I had not been involved in that science previously ... It was exciting learning about Antarctic science from very different fields.”

Luyt: “It was great to have many different experts giving their specialised input into the different facets of the expedition, like using remote sensing to aid in navigating of the ice, and to be able to learn why the region is so important to many different fields of science.”

Pooling research

What comes next?

Luyt: “First, there will be a cruise report detailing all the science involvement on the expedition including any initial results. Thereafter, there are bound to be multiple scientific journal papers published on the results of the data collected as well as enough data for the research of several master's and doctorate degrees.”

Hutchinson is currently working up the data, aiming to submit a paper for publication soon.

“I’m also designing a cross-disciplinary session proposal for a conference with colleagues I met on the ship, based on inspiration that I had from talking to them and brainstorming while at sea.”

Flynn: “We have already begun analysing our data. There is a lot to get through but hopefully we will be able to chat to some of the other research teams to see if our findings may be important for their research questions too.”

Story time

Besides their research, each returned with stories to tell.

Hutchinson shared an anecdote: “The SA Agulhas II broke away a massive chunk from an ice floe (we calculated the area to equal 28 500 000 rusks – our favourite ship teatime snack!) to free an AUV that got trapped underneath during a survey. We later named the AUV ‘Chippie’, after the carpenter from Shackletonʼs expedition who was known for being rather difficult and troublesome.”

Smith: “While searching for the wreck in the middle of thick pack ice, the ship created pathways of open water to prevent becoming beset. We soon noticed that hundreds of seals were both intrigued and incredibly delighted to see the ship. Between lazing on the ice, [and] play fighting with one another, [they were] diving into and out of the ocean from the surrounding ice, and swimming rounds underneath and around the ship.”

Flynn: “When we arrived at the coordinates of the Endurance wreck site, Captain Freddie Lighthelm, the ice captain, announced over the intercom (at 05:00 I may add!) that we had arrived at the wreck site, and ended it off with ‘Lekker, lekker!’. This reminded me that it was a South African ship and crew that got us there, which made me extremely proud.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Research & innovation