Maverick Citizen Op-Ed

Messaging during Covid-19: What can we learn from previous crises of infectious disease

The Covid-19 crisis has reinforced the global consequences of fragmented, inadequate and inequitable healthcare systems and the damage caused by hesitant and poorly communicated responses.

The discourse around the Covid-19 pandemic has rightly placed heavy emphasis on understanding (and limiting) the spread of infection, and the steps taken via the national lockdown to prepare our health systems for the expected spike in serious cases.

Each week seems to yield new models of infection trajectories and alternative scenarios for our future, often greeted by intense – and increasingly politicised – public debate about the economic and social costs of the pandemic and how they might be mitigated.

Sentinel data, including regional case numbers, fatalities and testing and recovery rates, are released daily, and have become critical barometers of the efficacy of the response to a dynamic and unpredictable situation that falls outside our experience.

The flood of information (and misinformation) is so large it can be difficult to determine the validity and value of many claims – often leading to a paradoxical tendency to opt for the most bizarre. Even the scientific community is overwhelmed by the number of new studies (almost 4,000 per week) claiming to have revealed something new or noteworthy about Covid-19 and the SARS-CoV-2 virus which causes it.

Against this backdrop, it is surprising that, with few exceptions (the World Health Organisation issued some guidelines), the need to ensure the quality and consistency of public health messaging and communication – a key component of a coordinated and coherent pandemic response – has been overlooked. In Africa especially, we are not strangers to communicable diseases such as HIV, TB, Ebola, Malaria and Influenza.

Here, we distil three key lessons those diseases have taught us about public messaging which could be usefully applied to Covid-19.

Trust is key. The rapidly changing landscape and overwhelming availability of information around coronavirus, combined with the speed and suddenness with which the pandemic hit, has elicited a collective sense of uncertainty and fear. If health communication around this pandemic is to be effective, a sense of trust in the messages and the messengers must be built. But how widespread is trust in health and science?

In 2018, the Wellcome Trust published the results of the first ever Global Science Monitor – a worldwide study on public perceptions and attitudes towards science and health. These data are highly relevant in the current situation and should be mined (and updated) at country level to determine how best to deliver relevant, credible public health messaging.

According to the Global Science Monitor study, only 18% of people worldwide have a high level of trust in science and health professionals.

Trust in science negatively correlates with societal inequality – the higher the level of inequality, the lower the degree of trust in science. Importantly, the report also uncovered that levels of trust in science are closely linked to levels of trust in national government and institutions.

For South Africa, this presents a significant challenge: trust in national institutions has been steadily eroded over the last few decades. In a country-level analysis, 23% of respondents to the Global Science Monitor in South Africa expressed “a lot” of trust in scientists and, positively, 74% of respondents would trust advice from medical doctors and nurses. How well this translates to trust in public health messaging, especially under the stress of an ongoing pandemic, is unclear.

Openness in acknowledging the general uncertainties inherent in even the best science is also critical to securing trust: in a pandemic, decisions are based on the best available evidence. The response must inevitably evolve with the data. “We’re trying to build the plane while we’re flying it”.

Messaging, therefore, needs to be clear and unambiguous while allowing room for adaptation as more information is gathered or the dynamics of the disease change. Balancing the scientific uncertainty with the need for absolutes in public health messaging is perhaps the greatest challenge. When done effectively, it allows for subsequent alterations without undermining credibility and impact. As noted below, collaboration with affected communities and investment in scientific literacy support this.

When the Covid-19 crisis subsides, we must embrace our mistakes and prepare for future pandemics by investing in our health systems. This must include improving health and science literacy throughout our population. In contrast to the certainty often assumed of modern medical science, the reality is that both practice and research are often messy and non-linear. Appreciating this fact is only possible through a greater public understanding of science and will contribute to improved epidemic readiness.

Context matters. Messaging should be tailored in a way that is relevant and resonates with the intended audience and should be delivered via sources accessible to that audience. South Africa has 11 national languages and it goes without saying that coronavirus information and messaging should be widely available in all of them. Moreover, messages should be prepared and modified for delivery across multiple platforms.

A 2018 Afrobarometer report suggests that the large majority of South Africans (74% in urban areas and 64% in rural areas) access daily news and information from television, followed by radio (57 % urban, 54% rural), and then social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter (40% in urban, 26% rural). The report doesn’t provide data for messaging apps like WhatsApp. However, the growing number of South African’s with access to smartphones (up to 80%) implies that these platforms are likely to evolve quickly into a popular and accessible source of information (and misinformation).

While mass communication is important, the power of formal and informal teaching and conversation in spreading information should not be undervalued. Unpublished data from a set of surveys conducted by Eh!woza in 2019 suggest that 70% of high-school learners in Khayelitsha first get information about TB from teachers, followed by 50% from family, friends and neighbours. This was different in Gaborone, with a similar study undertaken in January 2020 indicating that 80% of the young respondents obtained their first TB information from radio.

The reasons for the differing preferences for information source (and its implications for the levels of trust) require further investigation, but point to the need for region-specific tailoring of public messaging. Just as the clinical, humanitarian and epidemiological measures to combat the pandemic should be community-centered, so should public health messaging wherever possible.

Local political and social realities need to be considered and prioritised when developing messaging strategies, and a one-size-fits-all approach is likely to prove ineffective. Co-production and development of messaging in collaboration with communities was essential in dispelling myths around Ebola. Communities need to be consulted continually around information that is lacking, immediate fears and uncertainties that need to be addressed, and how best to deliver messaging. This engenders a sense of agency and collaboration; moreover, it raises an awareness of any underlying scientific uncertainties and the factors considered in formulating the final coherent message.

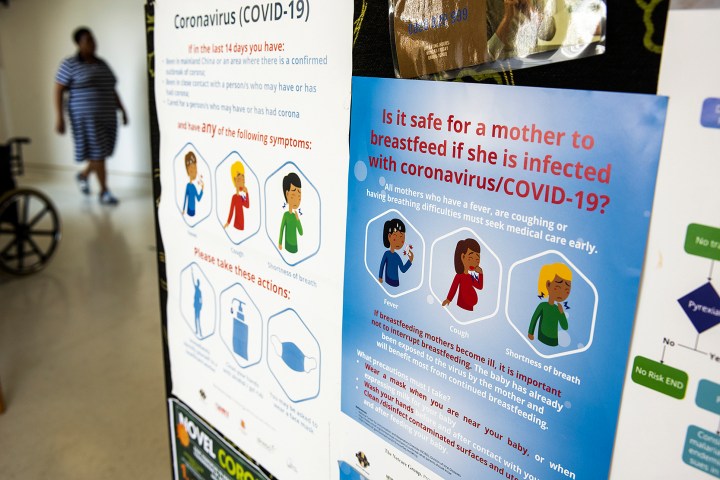

Respect for the target audience is also critical. This seems obvious but is often disregarded, especially in the quality of message delivered. The power of relevant visual literacy and semiotics should be applied in the communication of public health messaging. Moreover, experts in advertising, branding, communication and the arts and social sciences should be enlisted to determine which messages are most effective, in what context, and why.

Information as an antidote to stigma and misinformation

Combating stigma and misinformation is an essential component of all effective public health messaging. Research has shown that stigma results in fewer people seeking testing and care for diseases like HIV and TB, and that early on in the Ebola epidemic, messages that were too focused on the severity and lethality of the disease promoted a sense of fear and avoidance of healthcare.

There are concerning anecdotal reports that under Covid-19, people are not seeking care for endemic diseases such as HIV and TB, either out of fear or in the belief that lockdown prohibits or discourages clinic attendance and other health-seeking behaviour. For TB, there is the additional risk of stigma owing to the overlap in symptoms with Covid-19.

It is important to understand the source of misinformation and stigma. In addition to the spread of a clinically unpredictable virus, the WHO has called the pandemic an infodemic: “An overabundance of information – some accurate and some not – rendering it difficult to find trustworthy sources of information and reliable guidance.”

A study documenting a small set of responses to the pandemic in Cape Town highlighted the tendency for misinformation to emerge out of genuine attempts to distil accurate understanding from multiple sources.

Of course, misinformation can be highly politicised and used maliciously. Considered and well-delivered communication is key in limiting this potential. Moreover, new technologies, such as the infodemics observatory, can be used to measure the spread of information and misinformation as well as public sentiment around Covid-19, and messaging can be adapted accordingly.

For messaging and public engagement to be as impactful as possible, it is necessary that adequate resources are allocated to these activities. In turn, these interventions must be held to rigorous standards of assessment and accountability to ensure maximum impact.

Importantly, investing in engagement and messaging should not be reserved for times of crisis, but should be considered a sustained and critical element of a functioning public health system. Building trust in health information will not only equip us for future health crises, but will instil general positive health-seeking behaviour for existing diseases such as TB and HIV, hypertension, diabetes, mental health etc.

The Covid-19 crisis has reinforced the global consequences of fragmented, inadequate and inequitable healthcare systems and the damage caused by hesitant and poorly communicated responses. We have the opportunity to do this better and should make every attempt to do so. MC/DM

All four authors are founding directors of Eh!woza, a public engagement platform that engages young people from high burden areas with biomedical research around locally relevant infectious diseases, and provides a platform for young people to tell stories about the personal and social impact of these diseases.

Dr Anastasia Koch is one of the managing directors of Eh!woza. Prior to working fulltime at Eh!woza, she was a junior research fellow at the MRC/NHLS/UCT Molecular Mycobacteriology Research Unit (IDM, UCT), which she maintains in a part-time capacity. Anastasia’s biomedical research interests involve using genomics to understand the transmission and pathobiology of M. tuberculosis.

Bianca Masuku is a Junior Research Fellow at the Centre for Innovation in Learning and Training at UCT. She is also completing an interdisciplinary PhD at UCT examining how knowledge is configured and produced within the Eh!woza project, co-supervised by A/Prof Nolwazi Mkhwanazi of WiSER.

Ed Young is a conceptual/visual artist and one of the founding managing directors of Eh!woza. He has had multiple international solo exhibitions, group exhibitions and art fair presentations. Young is currently working towards an upcoming solo exhibition in Cape Town in 2020.

Prof. Digby Warner is the Deputy Director of the MRC/NHLS/UCT Molecular Mycobacteriology Research Unit which constitutes the UCT node of the DST/NRF Centre of Excellence for Biomedical TB Research and a full Member of the Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine (IDM). His research programme focuses on understanding the biology and metabolism of M. tuberculosis with a focus on DNA metabolism, vitamin B12 metabolism, developing pipelines for early stage TB drug discovery and understanding the mycobacterial factors that influence TB transmission in our high-burden settings.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider