Homo erectus skull find rewrites human history

08 April 2020 | Story Helen Swingler. Read time 7 min.

An international team of researchers that includes leading geologists from the University of Cape Town (UCT) unearthed and dated the earliest known skull of Homo erectus, the first of our ancestors to be nearly human-like in their anatomy and aspects of behaviour.

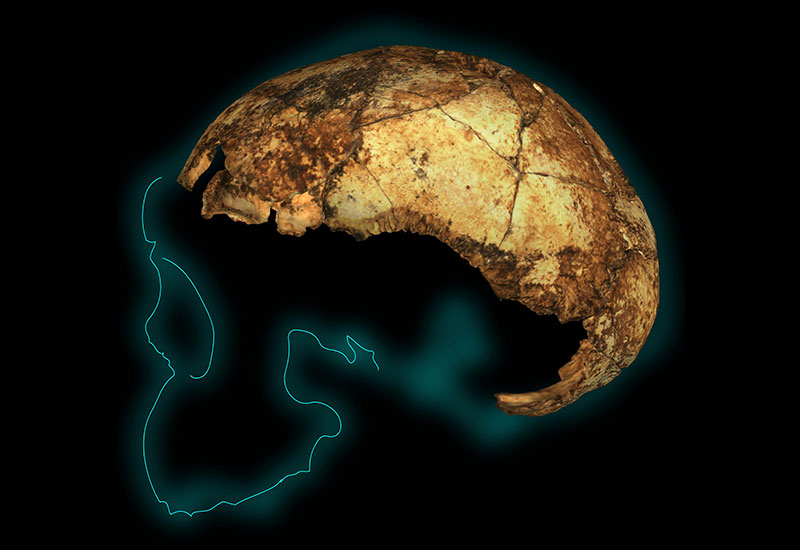

It goes by the lowly label DNH134, but the two-million-year-old fossil skull found at South Africa’s fossil-rich Drimolen cave system, north of Johannesburg, is rewriting humankind’s family history. Details and analyses of the find appeared in Science on Friday, 3 April.

Co-author Dr Robyn Pickering, director of UCT’s Human Evolution Research Institute (HERI), said the age of the DNH134 fossil shows that Homo erectus existed 100 000 to 200 000 years earlier than previously thought.

The skull, thought to belong to a two- to three-year-old female individual, was reconstructed from more than 150 individual fragments excavated in the Cradle of Humankind in South Africa over five years.

Discovered in 1922, the Drimolen palaeocave complex has yielded more than 155 hominin specimens, fauna, bones and tools. The complex is not far from Sterkfontein and is part of the Cradle of Humankind, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Quoted in a press release, project director and head of La Trobe University’s Department of Archaeology and History in Australia, Professor Andy Herries, said, “The Homo erectus skull we found, likely aged between two and three years old when it died, shows its brain was only slightly smaller than other examples of adult Homo erectus.

“It samples a part of human evolutionary history when our ancestors were walking fully upright, making stone tools, starting to emigrate out of Africa, but before they had developed large brains.”

Today we are the only human species on the planet, but two million years ago our direct ancestor was not alone, said Herries.

“We can now say Homo erectus shared the landscape with two other types of humans in South Africa, Paranthropus and Australopithecus. This suggests that one of these other human species, Australopithecus sediba, may not have been the direct ancestor of Homo erectus, or us, as previously hypothesised.”

Co-author Dr Justin Adams of Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute said the discovery raised intriguing questions about how these three unique species lived and survived in the landscape.

“One of the questions that interests us is what role changing habitats, resources and the unique biological adaptations of early Homo erectus may have played in the eventual extinction of Australopithecus sediba in South Africa.”

Co-director of the Drimolen excavation project, University of Johannesburg PhD candidate Stephanie Baker, said the discovery of the earliest Homo erectus marked an incredible milestone for South African fossil heritage, “and the country’s importance in the human story”.

Decades-long struggle

This Science publication has been years in the making, with the contributions of a large team very ably managed by Herries, said Pickering.

“In this paper some beautiful new fossils are presented and give us fascinating new insights into our own human story, but knowing how old they are was a key piece of the puzzle.”

Pickering’s hard-won expertise played a significant role in dating the discovery. The backstory is painstaking laboratory work over 15 years, adapting uranium-lead dating techniques to be applicable to the flowstone layers containing the fossils in caves.

Latterly this has been in the UCT Department of Geological Sciences’ highly advanced clean laboratory, “one of Africa’s finest laboratories for this kind of research”.

“There is more lead in a fingerprint than in my rock samples, so we need an ultra-clean lab to prepare the samples.”

“There is more lead in a fingerprint than in my rock samples, so we need an ultra-clean lab to prepare the samples. We’ve struggled for decades to date the South African fossils, but now we have a range of suitable techniques, and it’s possible to push back the first appearance of our earliest ancestors from the Cradle.

“Uranium-lead dating is similar to radiocarbon dating, but uranium has a much longer half-life, so we can date rocks which are much, much older – millions and even billions of years old.”

As director of HERI, Pickering’s own research tries to understand where, and most importantly when, our early human ancestors evolved.

“We’d like everything to be like a simple layer sandwich, with layers stacked one on top of another, but caves are complicated.”

“We’d like everything to be like a simple layer sandwich, with layers stacked one on top of another, but caves are complicated. The caves in the Cradle were also mined for the speleothems [calcium carbonate], so we often have little left to work with. We have to be detectives, making careful field observations and piecing the bigger picture back together.”

UCT postdoctoral research fellow Dr Tara Edwards was part of the geology and dating team that reconstructed how the fossils ended up in the cave and checked that the dating methods were accurate. This is her first Science paper.

Edwards’ primary contribution to this project was her expertise in speleothem petrography – looking at very thin slices of cave deposit, or flowstone, under the microscope.

“This way we can tell a lot about what was happening in the cave and the external environment when that deposit formed. In this instance it was very important for understanding how the Drimolen cave infilled. We need to understand the way the cave filled up in order to contextualise and robustly date the fossils.”

When Edwards first visited the site as a first-year PhD candidate, she knew it was going to be a challenge.

“I had never seen anything like it. I was used to working in caves with roofs!

“The main challenge anyone faces working at these heavily eroded palaeocaves is understanding the stratigraphy. This is because everything is tied to stratigraphy – site formation, dating and, of course, the fossils.”

Evolving diversity

The finding highlights the region as a treasure trove for understanding human evolution, but this project and paper highlights other aspects of human change in a contemporary context.

Baker pointed out that this project is the first major breakthrough in hominin research with a director who is a woman and a South African.

“The story of hominin evolution is once again changing, but importantly for us locals, so is the field.”

“The story of hominin evolution is once again changing, but importantly for us locals, so is the field.”

Pickering noted that there are few South Africans, or students, among the authors.

“Of the 26 authors, only six are women and all of the authors are white. Bringing diversity to palaeoanthropology teams working in South Africa is one of the core missions of HERI. Training up young, black South Africans and amplifying their voices is at the centre of what we do.”

Edwards agreed that the historical and continuing inequity in palaeoscience must change. She is a first-generation university student and the first in her family to graduate from high school.

“I would like to encourage other first gens, firstly by recognising that while academia as a system and institution was not designed or intended for us, we are allowed to be here. We can carve out a space for ourselves through persistence and by doing so, offer guidance and support for others.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.