Iconic conifers under threat

21 December 2016 | Story Ambre Nicolson.

A team of UCT ecologists has used repeat photography to study the decline of the critically endangered Clanwilliam cedar. Their findings, published last month, suggest that climate change and more frequent fires are threatening the survival of this iconic conifer.

The Clanwilliam cedar (Widdringtonia cedarbergensis) is a familiar sight along the rocky cliff faces of the Cederberg. These giants grow to heights of 20m and often have a lifespan of 400 years. Sadly, these days there are far fewer of them to be seen in the region.

Now, thanks to a collaboration between Professor Timm Hoffman, director of the Plant Conservation Unit (PCU), and Associate Professor Ed February from the Department of Biological Sciences, the decline of this conifer has been measured using repeat photography. February's interest in the species stretches back over two decades, and the team also made use of Hoffman's collection of historical photographs, archived at the PCU.

Hoffman and a previous Masters student at the PCU, Daniela Bonora, went out on the first expedition to the Cederberg in 2007 to take repeat photographs of W. cedarbergensis. This was followed up by current PCU Ph.D. student, James Puttick, and PCU research associate, Sam Jack, returning to the Cederberg to take the bulk of the repeat photographs in 2012. Lastly, Jack and Joseph White, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Biological Sciences, went to take the remainder of the photos in 2013, which completed the data used in the publication.

The team used 87 pairs of historical and repeat photographs, taken between 1931 and 2013, to analyse the changes in W. cedarbergensis demography over the course of the 20th century.

Discovery of a significant decline

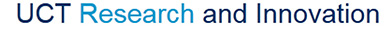

The above composite image was taken at Vogelgesang near Kleinvlei in 1941 and again in 2007. The green dots show living trees, the orange dots show skeleton trees, the yellow dots show recruited trees (saplings that have grown to the point where they can be considered to have joined the population); the red dots show trees that have died.

Only three of the original 17 living trees seen in the first image were still alive in 2007, and sadly, the image is representative of the team's findings as a whole: from an initial total of 1 313 live trees in historical photographs, 74% had died and only 44 had recruited in the repeat photographs, leaving 387 live individuals.

Explaining the collapse

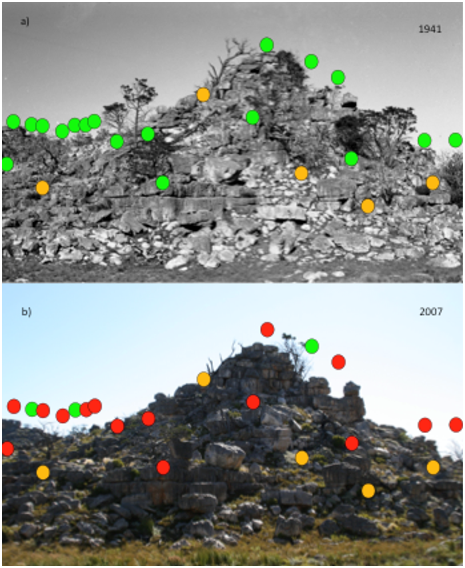

Images by Howes-Howell (1951) and James Puttick (2012).

Images by Howes-Howell (1951) and James Puttick (2012).

This image, also taken in the Vogelgesang area but at a different site, shows eight living trees in the first image, with seven living trees and two dead trees (one tree recruited and died in the intervening period) in the second. The team found that trees growing at higher, cooler locations were not as badly affected as those at lower, hotter altitudes.

White explains that there is no single reason for the near collapse of the species: “Our model demonstrates that mortality is related to greater fire frequency, higher temperatures, lower elevations and less rocky habitats. We also found that those trees located on east-facing slopes were most likely to survive.”

According to White, climate change also disproportionally affects conifers. “Conifers appear more vulnerable than flowering plants (or angiosperms) to climate-induced drought stress, because of a process called 'xylem cavitation',” he explains. “What happens here is that the water transport system in the tree becomes blocked with air bubbles because of a lack of available water. If this isn't repaired, the tree use water effectively in the future.”

Why the Clanwilliam cedar?

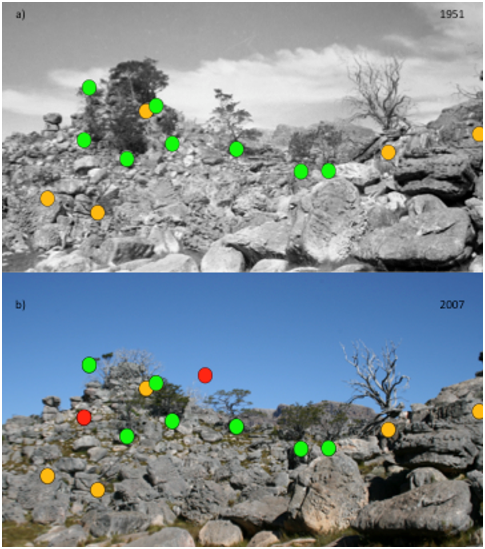

Photographs by Taylor (1986) and Jack (2013).

Photographs by Taylor (1986) and Jack (2013).

The above image shows a mature Widdringtonia cedarbergensis under Shadow Peak in the Welbedacht area. The image shows that of the two living trees recorded in 1986, only one survived, with one recuit.

According to White, the team focused on the Clanwilliam cedar because of the critically endangered status of the species, its longevity, as well as the ease with which individuals could be identified in the historical and repeat photographs. “It is the dominant tree in the Cederberg and there are no equivalent sized angiosperms,” he says. “Other indigenous conifers, such as the closely related Widdringtonia nodiflora – the mountain cypress, which is found in cooler, wetter habitats such as at Bainskloof and Du Toits Kloof – and Widdringtonia schwarzii, the Baviaanskloof cedar, are not as vulnerable to population collapse as the Clanwilliam cedar,” he says.

What does the future hold?

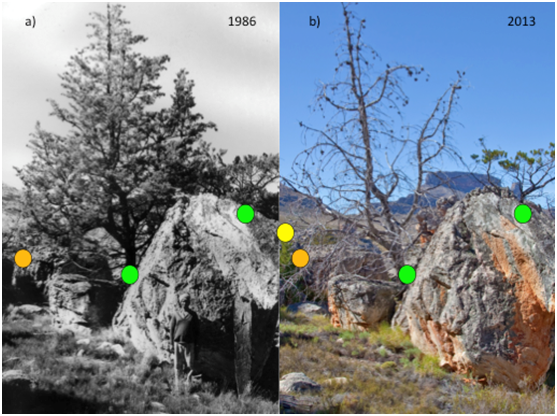

Photographs by Ken Howes-Howell (1931) and James Puttick (2012).

Photographs by Ken Howes-Howell (1931) and James Puttick (2012).

The image above, taken at Cathedral Rocks near Middelberg in 1931 and 2012, is an example of one of the most worrying aspects of the team's discoveries: the lack of adequate recruitment, or sufficient young trees surviving. The image shows that, of the original 10 living trees at the site, only two remain, with no recruits.

“The future for the species is bleak,” says White. “Without an urgent, sustained and well co-ordinated intervention, and if the high rate of mortality and low rate of recruitment continues, the species will probably not survive in the wild into the next century.” “Luckily there are many stakeholders that are interested in the conservation of the species and with some luck and a lot of effort, hopefully the Clanwilliam cedars' fortunes can be turned around.”

Associate Professor Ed Februrary is a member of the Next Generation Professoriate.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.